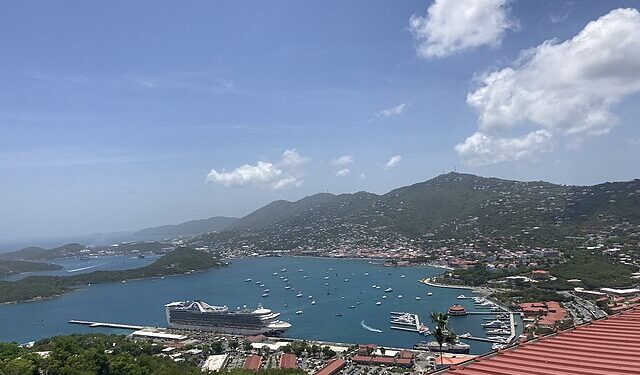

Traces of Denmark’s 250-year imperial reign are still visible on St. Thomas, St. Croix, St. John, and the smattering of tiny islets that today make up the U.S. Virgin Islands reports Karrisa Waddick form the USA Today.

Cities and street signs bear Danish names, like Frederiksted; buildings feature yellowish-red bricks brought across the Atlantic by boats; and the stone facades of sugar plantations where enslaved Africans were forced to labor still stand.

They’re interspersed with evidence of the islands’ vibrant Caribbean culture, from colorfully costumed dancers to drum-driven melodies, and the McDonald’s and Home Depot stores that reflect its now-century-long status as an unincorporated territory of the United States.

As President Donald Trump negotiates a “framework of a future deal” with Denmark for access to Greenland, some residents of the tropical territory are reminded of what they see as a replay of their own past.

“History never repeats itself in the same way, but it shows up in a different form,” said Stephanie Chalana Brown, an Afro-Caribbean visual historian with deep roots in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Brown said her ancestors were among the first enslaved by Danish colonial powers, and she is now among a cohort of people working to secure reparations from Denmark.

As slaves, then as residents of the Danish-turned-United States territory, Brown said her relatives were sold without their consent.

A century later, she worries that Greenland’s residents are facing the same threat her ancestors did: not having a seat at the table in decisions about the future use of their lands.

“I understand it because the same thing happened to my relatives,” Brown said. “I don’t want to see it happen to another place.”

The annexation of the Virgin Islands

More than a century ago, President Woodrow Wilson bought the islands, then called the Danish West Indies, from Denmark for $25 million after threatening to take them by force. During a European war, the U.S. sought greater influence in Latin America.

Like Trump with Greenland, Wilson pursued the islands for strategic reasons: securing new trade routes and blocking adversaries.

The nation’s rival then wasn’t China or Russia but Germany, the aggressor in World War I.

The roughly 26,000 inhabitants scattered across St. John, St. Croix, and St. Thomas in 1917 were not given a say in the acquisition.

Virgin Islanders reflect on Greenland

For Brown and other Virgin Islanders with ancestry tied to Danish colonialism, the recent discussions over Greenland’s future have sparked heightened empathy and concern for the 57,000 inhabitants of the 836,000-square-mile island.

“Is he bringing them to the table to talk about policies?” she asked of Trump’s plans for America’s military footprint on the island.

“Those things weren’t extended to Virgin Islanders.”

Most Greenlanders are Inuit, an Indigenous people who also live in Alaska and Canada. Greenlandic, the language they speak, is vastly different from Danish. And their traditions are distinct from those found in Denmark, Western Europe, and America.

If the United States builds up its military presence on Greenland, Brown said she worried the island could go through a process much like what happened in the Virgin Islands: American culture gradually becoming more dominant and changing local traditions.

“You see the washing of our children’s identity away, where you know they’re learning about American culture from the influence of things like television and radio,” she said. “We are losing our own Caribbean identity. I hope that doesn’t happen to them as well,” Brown said of Greenland.