Areas that did not fit European concepts of land use were often described as “unused,” “wild,” or “uninhabited,” and considered open for acquisition.

US President Donald Trump described Greenland as “a piece of ice” during a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, a remark that overlooked the island’s long history of habitation and its population of more than 56,000, most of whom are Inuit.

The comment highlighted a familiar pattern in which colonial powers have imposed their own concepts of land ownership on places with established local systems.

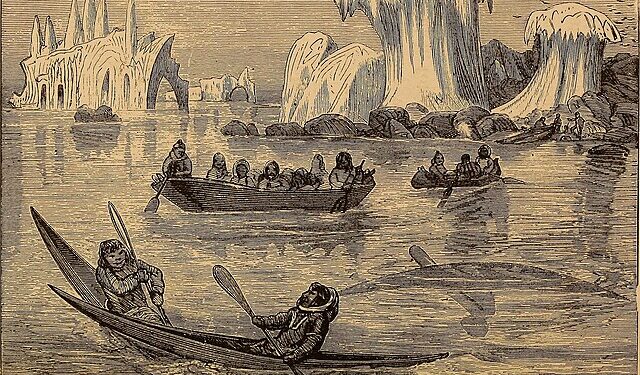

Inuit in Greenland regard land as a shared resource, not something to be bought or sold. Many Indigenous societies have traditionally managed land through seasonal hunting, harvesting, and the protection of water sources and ancestral sites.

European empires, by contrast, treated land as property that could be claimed, bought, or transferred.

Areas that did not fit European concepts of land use were often described as “unused,” “wild,” or “uninhabited,” and considered open for acquisition.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Australian Historical Studies revealed that in the 18th century, British officials used the term “uninhabited” to describe land without a sovereign or “civilised” government, not necessarily land without people.

This interpretation meant that communities could have been living on, farming, and naming places for thousands of years and still not be considered “inhabitants.”

This mindset influenced how colonial powers justified their control over various regions. Here are a few examples:

Alaska: When Deals Ignored Indigenous Interests

In 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire for $7.2 million. The agreement, arranged by US Secretary of State William H. Seward, was made without consultation with Alaska Natives, who had lived in the region for at least 10,000 years.

Their way of life, based on seasonal hunting, fishing, and gathering, was not considered in the transaction, which treated Alaska as a commodity exchanged between empires.

Australia: The Myth of “Terra Nullius”

For over a century, British authorities labelled Australia “terra nullius,” Latin for “land belonging to no one,” despite the presence of Aboriginal peoples for at least 60,000 years.

For Aboriginal peoples, “Country” is a holistic concept that encompasses land, water, sky, and ancestral responsibilities. Their land management practices, such as controlled burns, were not recognised by the British as signs of a “civilised” society.

As a result, in the 18th century, British officials declared the continent “terra nullius,” a doctrine that remained in Australian law until it was overturned by the High Court in 1992, which finally recognised the traditional land rights of Indigenous Australians.

North America: Mobility Versus “Improvement”

European settlers arriving in the Eastern and Central United States in the 1600s encountered Indigenous nations with established systems of seasonal migration for hunting, harvesting, and ceremonies.

European legal frameworks, influenced by the philosopher John Locke, held that land became property through “improvement” such as farming or building. This view shaped early US legal concepts of land ownership.

In 1823, the US Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans could occupy their land but could only sell it to the federal government, basing the decision on the “Doctrine of Discovery,” a principle that gave Christian European nations ownership of non-Christian lands upon “discovering” them.

This precedent continues to affect Indigenous communities, as seen in the 2016 Standing Rock protests, where the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s concerns about water and sacred sites were not upheld by federal agencies.